“Don’t worry. All this positivity won’t last. It’s just the fish talking.”

“That’s what I’m worried about.”

“Understandable. Talking fish would be terrifying.”

Cara stared. “Did you just make a joke?”

–TWIN

Can I make the least controversial statement ever? The world sucks these days. It’s not just lately that everyone with any power is using it to oppress anyone with less power. The world has always been like that. But now I’m one of the grown-ups, and the weight of it settles on me in a new way. I’m the girl who could always fall asleep (anytime, anywhere), and now I have nights where I lay awake with anxiety gnawing inside. I know I’m not alone.

I’ve said before that there’s no running away from negative emotions, that they have to be faced and given a name. I believe that with all my heart.

But I’d be lying if I stopped there. Because naming our pain and fear is only the beginning.

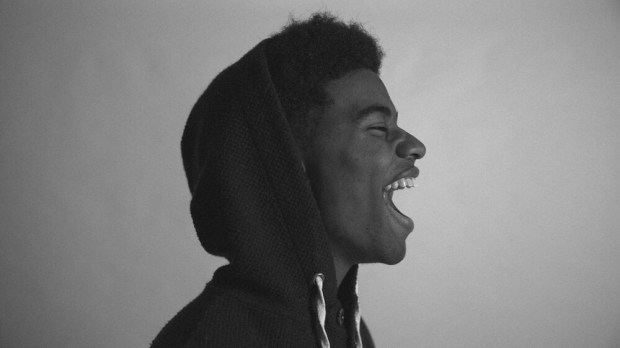

The critical next step is to laugh at them.

Laughter and tears are both responses to frustration and exhaustion. I myself prefer to laugh since there is less cleaning up to do afterward.

–Kurt Vonnegut

My husband and I have been hanging out with hurting people for almost two decades now. We’ve seen some serious horror and lived through some of it ourselves. Sometimes people ask how we’ve kept doing it. Of course, there’s no real answer to that. You keep doing something by, well, not stopping.

But if you want to know one the ways we stay sane, I can tell you: we laugh.

When I’m in bed with a racing mind, my husband makes up songs about our dog. They are epically (comically) bad. When he’s carrying the weight of the world on his shoulders, I make fun of the weight or the world or sometimes him. Only because he likes it. We trade memes. We watch a lot of stand-up comedians and a lot of SNL. Please get us started sometime on our favorite sitcoms.

Sure, sometimes we’re laughing to take our mind of things, watching comedy to escape reality, but our favorite laughter is the kind that cuts reality open rather than denying it. Because laughter is a weapon. It’s a shield to protect us from despair and a sword to skewer our dread.

It was a lot harder to believe you might lose a war when you could still laugh on the morning of the last battle.

–Alwyn Hamilton, Hero at the Fall

Laughter doesn’t just represent a hope that we will conquer our present pain or difficulty; laughter is a victory itself. Laughter says, “I may not be able to control this, but it doesn’t control me either.” If I can laugh, I am still myself. No matter what has happened or will happen, those things don’t define me.

Which is why when I sit with a devastated friend and we laugh at the very situation that’s caused them pain, we almost always say, “This isn’t really funny,” but we keep laughing anyway. Because we can if we want to. I may have no choice but to cry but I ought to at least have the choice to laugh. Is it inappropriate? Yeah. But it wasn’t appropriate that any of this crap happened in the first place. The S.S. Appropriate has already sailed.

And that’s how you go on. You lay laughter over the dark parts. The more dark parts, the more you have to laugh. With defiance, with abandon, with hysteria, any way you can.

–Laini Taylor, Strange the Dreamer

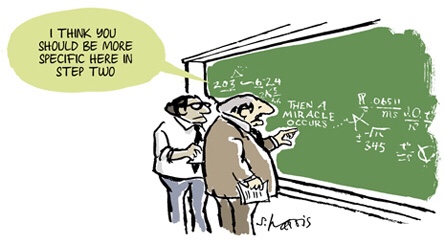

But how do you do it? How do you turn to laughter instead of tears? Obviously, you can’t always get there. Sometimes pain is too great or just too fresh. Some things are so horrific, it feels like a betrayal to laugh in their face. But then, it’s those very things that later breed the darkest and most important laughter.

It’s an issue of perspective. Laughter is powerful because to laugh at something, we have to step outside of it. To the person falling, the experience is only pain. To the one watching from a distance, it’s hilarious. Have you ever seen someone walk into a spider web when you are too far away for the web to be visible? In a split second they go from walking normally to gyrating in a dance of waving arms and whipping head. There is no way not to laugh, even though the same thing has happened to you and you remember the horrible sticky feeling. Perspective shows us that though one side of the experience is an unpleasant shock, the other side is a spontaneous and ridiculous dance.

My point here is not that we should keep people at a distance and laugh at them. On the contrary, when we are watching someone fall, we should put ourselves in their place and empathize with their pain. But that same thing can be done when we are the ones falling. We can put ourselves the shoes of an observer and let ourselves laugh at the undignified mess of our own troubles.

That kind of perspective takes practice; you have to consciously choose to engage it. I read an article a couple of years ago in which a famous preacher quoted one of his old professors, giving a series of resolutions for maintaining mental health. The lecture in question was given the year I was born, so I didn’t have high expectations for his understanding of the topic, but what I read delighted me, and I’ve thought about it often since then. Resolution #1 has become one of my regular practices.

1. At least once every day I shall look steadily up at the sky and remember that I, a consciousness with a conscience, am on a planet traveling in space with wonderfully mysterious things above and about me.

–Clyde Kirby, English professor (from a lecture in 1976)

There’s the perspective we need to laugh on our darkest days. I am one tiny creature in a vast universe. This ball spins and spins in a giant vacuum, and somehow I walk its surface and don’t fall off. On the other side of the world, there’s a woman my age walking upside down and convinced that she’s the one who is right side up. We hurtle through space around a flaming ball, surrounded by dangers that could cause our immediate death. And here we are, walking around in our thin layer of breathable air, content to ignore all of it. The whole thing is deliciously ridiculous.

Truthfully, Professor Kirby’s resolutions are wonderful, and I highly recommend you click through and read them all. I don’t share his disdain for introspection, but I do believe in the importance of not getting lost in it. We balance introspection with intentional engagement in the world in all its intricate variety. In that balance we find joy. I especially love resolution 6:

I shall open my eyes and ears. Once every day I shall simply stare at a tree, a flower, a cloud, or a person. I shall not then be concerned at all to ask what they are but simply be glad that they are. I shall joyfully allow them the mystery of what Lewis calls their “divine, magical, terrifying and ecstatic” existence.

–Clyde Kirby

Every time I read that resolution, I feel my breathing ease. The freedom to see a tree swaying in the wind and not wonder if its beauty is enough to counterbalance the horror in the world. To not think about how I should really do more to take care of the trees in my yard. To not think any important thoughts at all, but just to look at the tree’s motion and feel the satisfaction that such a thing exists in the world. I can listen to my cat purr or breathe in the fall air, and it doesn’t have to mean anything. It can just be joy.

That’s the lesson of inappropriate laughter. Joy can liv e alongside sorrow and laughter can live alongside pain, and the two don’t have to be at war. They can just be.

And I can take the weight of the world off of my itsy-bitsy shoulders and laugh that I ever thought I could lift all that anyway.